How to dash hopes that civil wars can be ended with honor and rehabilitation.

After negotiating a comprehensive peace agreement with the FARC-EP guerrillas and signing in on September 26th, 2016, the president of Colombia Juan Manuel Santos decided to submit the agreement to a referendum. He didn’t have to, but he preferred to go that way to enhance the popular legitimacy of the settlement bringing to an end Latin America’s longest civil war.

After the polls closed on October 2nd, 2016 with a low turnout of 37,4%, the NO votes opposing the peace agreement marginally outnumbered the YES votes: 6,431,376 vs. 6,377,482, out of a total potential electorate of 34,899,945.

The rejection came as a cold shower on the hope raised by the possibility of ending over 50 years of war that victimised around ten million people between forcibly displaced peasants, killings, disappearances, wounded and maimed.[1]

While waiting for a detailed breakdown of electoral results by municipality and analysis of voting pattern, we can advance here two comments. The first refers to a meme that was circulated on twitter with regard to the supposed pattern of vote:

Important: the areas of Colombia that faced the worst of the civil war voted ‘Yes’ for peace. Areas least hit voted against the deal.

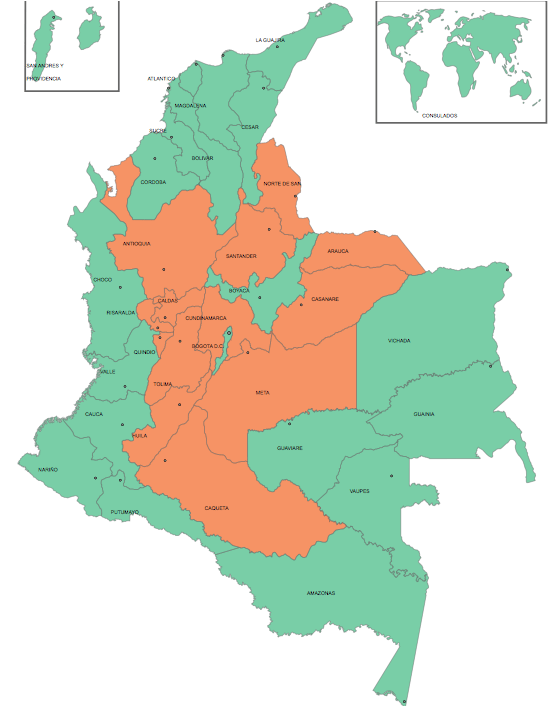

In general, the low turnout make these kind of associations shaky at best since they do not capture the intentions or expressed will of two third of the adult population. Besides, the NO votes prevailed, again against the background of low turnout, in the departments of Antioquia (NO 1,057,518 — YES 648,051), Norte de Santander (NO 282,183 — YES 159,255), Meta (NO 191,489 — YES 109,676), among others. Describing Antioquia, Norte de Santander and Meta as among the areas ‘least hit’ by the war is quite an understatement.

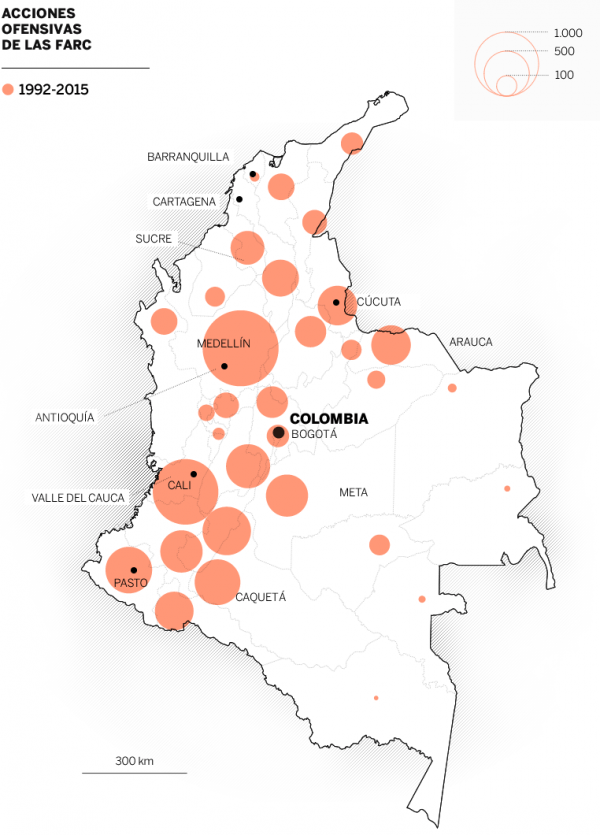

[El País, acciones ofensivas de las FARC 1992-2015]

[Green: departments with a plurality for YES vote. Orange: departments with a plurality for NO vote. Source: http://plebiscito.registraduria.gov.co]

The second comment refers to the contradiction between seeking for popular legitimacy while at the same time giving activist minorities a disproportionate electoral and political leverage. Let’s consider the full results of the referendum:[2]

Threshold: 4,536,992

Total poll stations: 81,928

Informed poll stations: 81,916

Total potential electorate: 34,899,945

Blank votes: 86.243 0,2% of total electorate

Null votes: 170.946 0,5%

Valid votes: 13.066.047 37,4%

NO votes: 6.431.376 18,4%

Now one may wonder about the political wisdom of upending a historical agreement on a wafer-thin margin of 54 thousand votes in a low turnout election in a country of 35 million voters. If the president and his adviser were searching for popular legitimacy, well this is quite the opposite. But there is method in this festival of unintended consequences.

The electoral law n. 134 of 1994 regulating referenda prescribed a minimum threshold of 50%+1 (or ‘the majority of the electorate’) for a referendum to be valid. However, the same president Santos crucially had this threshold drastically lowered to a bare 13% of the electorate – or around 4.4 million votes – during preparations of the peace agreement referendum.[3] Well, technically the government claims that they did not lower the threshold but switched from a turnout-based threshold to one based on the absolute number of cast votes.[4] But this is a sort of sleight of hand. In any case it means that the President was ready to declare victory with only a fraction of the electorate endorsing the peace agreement. Not exactly a resounding popular legitimisation of a historical passage.

Probably the President was motivated by the historical precedents in previous referenda or other special elections (e.g. the constituent national assembly) that saw the electoral turnout plunging from 68% in 1957 to 39% in 1988, 19% in 1990, 25% in 1992. The turnout in parliamentary elections used to float around 35-40%, with a higher participation in presidential elections (45-50%).[5] Overall, the chances to have the referendum validated by ‘the majority of the electorate’ casting their vote looked slim indeed. But resorting to a dramatic lowering of the validity threshold indirectly offered the vocal, activist minority coalesced around the former president Alvaro Uribe Velez opposing the peace agreement an unexpected leverage.

Acknowledgements

Cover photo credit: Santiago La Rotta, El árbol del fin del mundo, Páramo. Colombia. 2013. https://flic.kr/p/nie5eb

References

El País, Colombia: camino a la paz.

Reference link ↩︎Registraduría Nacional del Estado Civil, resultados preconteo plebiscito 2 de octubre 2016.

Reference Link ↩︎Se necesitarían 4,4 millones de votos para aprobar acuerdos con Farc, El Tiempo, 12 de noviembre de 2015.

Reference Link ↩︎Acuerdo de paz, plebiscito.

Reference Link ↩︎RagazziConsulting, Colombia Database.

Reference Link ↩︎