On November 3rd 2020, the Americans will choose their next president and the implications will influence the rest of the world’s political and economic affairs for the next four years. In this context, it seems relevant to discuss the negotiations for the renewal of the START Treaty between the US and the Russian Federation, and China’s current role in the nuclear strategic power play.

After the signing of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) between the US and the USSR, which prohibited possessing, producing, or flight-testing middle range missiles (500–5,000 km), and the end of the Cold War which brought the entering into force of START I and II, the global warheads were reduced from 64,449 in 1986 to 11,635 in 2009. A nuclear war had been avoided and all seemed to be going well. Until it wasn’t.

After months of back and forth between Moscow and Washington, in February 2019 the US suspended their compliance with the treaty, Russia followed suit, and on August 2, 2019 the US formally withdrew from the INF. The decision was controversial as from that date on, both countries would be able to build and test intermediate range missiles, putting in grave danger the balance attained after the end of the Cold War. As the new START, the last nuclear treaty still in force is to end next year, negotiations have started again in June 2020 to reach an agreement.

At the time of the signature, the INF treaty was a mutual accord between the two blocks governing the world, but one might wonder whether an agreement between Russia and the US in today’s multipolar world is as relevant as it was in 1987. Probably not, because at least someone is missing. The 1990s and the 2000s saw the rise of China as an economic power and as an aspiring normative power, meaning, citing Manners, championing a set of values regulating international interaction, alternative to the US-led world order.

But how is the Chinese power relevant with respect to the new arms control treaties? While the PRC has initiated its nuclear weapons programme in the mid-1950s, after the Korean war, the Chinese nuclear doctrine has always been somewhat peculiar. It is based on a no-first use policy (NFU), which made the country unique. Immediately after the first test in October 1964, the Chinese government pledged to “not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states or nuclear-weapon-free zones”. This makes it clear that Beijing had and still maintains an exclusively defensive policy, meaning that the only role nuclear weapons play in China’s strategy is to deter other states from attacking; for the PRC it is not necessary to engage in a nuclear race with other countries, but to avoid the full spectrum of a nuclear war, it is enough to have the capability of a second strike targeting a few big cities. Another implication is that China has used the strategy, among many things, to gain international recognition as a globally responsible nuclear power.

China’s adherence to the NFU policy has been questioned numerous times by Western powers but the PRC has never given any concrete indication, both in official documents and in practice, that it was going to stray from its self-set standards. The evidence can also be seen from the fact that the majority of the warheads the PRC has built and tested are strategic and not tactical1, which means that they are mounted on long-range intercontinenatl ballistic missiles (ICBM) designed for mass destruction to be used with a premeditated war plan and already established targets such as enemy cities and military bases.

China has been steadily trying to improve the quality and the quantity of its nuclear weapons over the decades, but the slow pace of the modernization, that doesn’t compare to its economic growth in the last thirty years, suggests that nuclear weapons haven’t been a priority for the different leaderships and that their main aim is deterrence. As a matter of fact, after a half-century of efforts, China’s nuclear arsenal remains smaller than the US nuclear arsenal was in 1950.

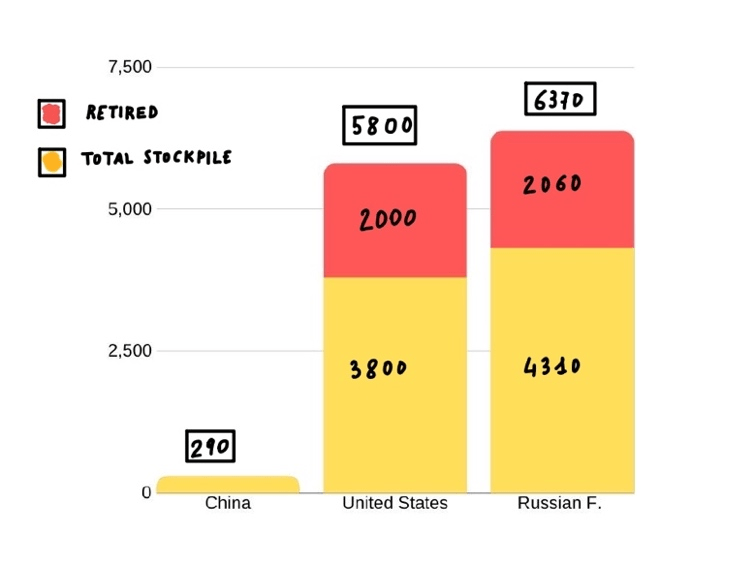

Even though the US Department of Defense in its 2018 Nuclear Posture Review did explicitly claim that China is also expanding and modernizing its non-strategic nuclear weapons, the fact that Beijing doesn’t seem to want to deviate from its NFU strategy is highlighted in the 2019 report by the Atomic Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The document states that China has approximately 290 nuclear warheads (total), which is an extremely low number if compared to the US (5,800) and Russian arsenals (6,370). The report does admit that China is modernizing its arsenal and that could soon become the third nuclear power in the world but stands on the fact that there is no suggestion China is going to deviate from its longstanding approach.

The nuclear debate in the PRC has really taken off since the 1990’s with a varieties of opinions challenging the traditional no-first-use doctrine. On one end of the spectrum a few argue for the unilateral discarding of nuclear weapons altogether for strategic reasons. The opposite position seems relatively more popular: giving up the NFU to enhance nuclear deterrence and bypass the centralized decision making in case of crisis that the policy entails. The second option was supported not only by some members of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) but also by part of general public, on the tide of the rising Chinese nationalism. However, these opinions are the minority and the Xi leadership seems to prefer to stick to the NFU policy for the foreseeable future, at least according to the declarations of government officials: the discarding of the NFU would have important consequences, especially in the economic domain. It would force the PRC to expand dramatically its arsenal, which would be extremely expensive as China would have to play a catch-up game in a matter of years, and the recent developments due to the repercussions of the forced lockdown, which caused the economic growth to shrink by a 6.8% in the first quarter of 2020 compared to 2019, make it even more unlikely. Moreover, a new arms race would risk affecting regional and global stability and, as collateral damage, ruin the image of responsible nuclear power China has strived to build since the very first day, which today can be well included in its normative strategy. For this reason, the majority of Chinese analysts don’t think there is going to be any shift in the PRC’s nuclear strategy anytime soon, only envisioning a first-use in cases of existential threat, namely: the proclamation of Taiwan’s independence, an attack to China’s nuclear arsenal or to the center of command and control, an attack of conventional force comparable to a nuclear attack or in case of interference to change the current regime.

The Trump administration has announced that in the “New Era of Arms Control”, the negotiation table should include both Russia (not particularly inclined to strike a deal, since its nuclear arsenal is one of the critical assets that allows the Russian Federation to maintain its great power mantle) and China. Problem is: China definitely doesn’t want to sit at it.The US is determined in involving China in the talks, as the final treaty would involve a more structured mechanism to ensure compliance, claiming the necessity of it as some reports described nuclear tests are part of this strategy. It is exactly for this reason that China is reluctant to join: the PRC is inexperienced on negotiations and on the control mechanisms that a new treaty would entail and is afraid that the required transparency could endanger its second-strike capacity. China’s stance has been clear in the declarations of State Councilor Yang Jiechi on the multilateralization of the INF Treaty in 2019, where he reiterated that China opposed to the initiative. From a Chinese perspective, survivability is the crucial passage for China’s nuclear arsenal in case of a second-strike and for this reason it is an imperative to not let other countries know the exact number, quality and location of deployment of its warheads. The historical tradition of the NFU policy, the reputation damages China would incur as it would be perceived as switching from a defensive to an aggressive posture in the international arena, plus the extreme economic effort that would be needed to catch up to the other nuclear superpowers suggests that China is not going to be changing its posture anytime soon.

Of course, many more factors have to be included in the analysis, including the present and future attitude of the US towards China, which has definitely become increasingly more aggressive in the wake of the pandemic and the results of the US elections in November. The most probable outcome of a direct clash between the two superpowers is a harsher commercial war, but never say never. Especially when nuclear weapons are concerned.

1 Tactical weapons are, instead, short-range and are to be used against moving targets in the battlefield.

Cover photo by Gord McKenna, Titan II Nuclear Missile, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, 2013