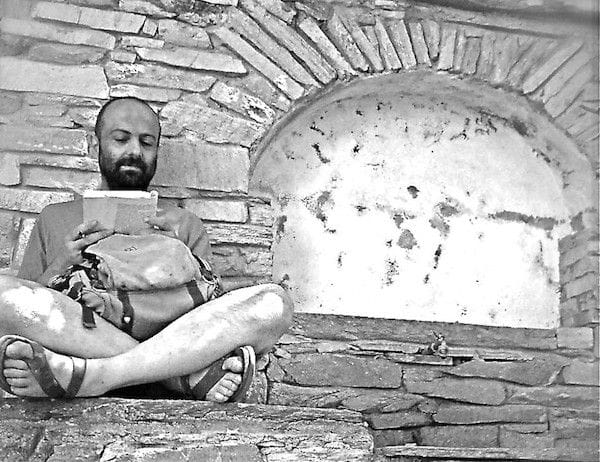

Luca Rastello, journalist and writer. 9 July 1961 - 6 July 2015.

The curtain opened and he passed away. Luca Rastello’s corageous work must be known across all those borders and orders he’s been transgressing.

With the exception of his I am the market: How to smuggle cocaine by the ton in five easy lessons, a provocative deep immersion in the collusive and criminalized dynamics of which the narco-business world is imbued, the name of Luca Rastello is little known beyond the Italian borders. His books and articles are nowhere to be found in the ‘easy Italy for export’ package. On the face of it, he’s little known even within national borders. Although he worked for the liberal national daily La Repubblica, there has always been a hyatus between Luca’s dissection of reality and the Italian mass media circus, always so ready to bow to new icons. Likewise, his defense of those sacrosanct individual rights for which human collectives get mobilized and struggle never watered down his unabated, strong criticism of how collective solidarities and social rights are being betrayed by individual self-indulgence, abstract desiring and narcissistic vested interests.

On July 6, 2015, Luca left us. The curtain opened and he passed away. Every single day, during the past 10 years he decided that he would not become the cancer that struck him at the age of 43, passing him a medical verdict of ‘a few weeks left to live’ while he was taking his family on holiday.

Luca loved to play with the curves of time, beginning with the time of narration. He never ceased to travel, rubbing his shoulder with dusty and uncomfortable realities. My last journey next to him was on a night-train Odessa-Simferopol, exploring tensions that virtually nobody would be interested in reporting in those times, but that would detonate only a few winters later. We didn’t write a line about that trip, we just travelled to take mental notes of a possible ethnography of change. After that he travelled to Argentina, Nepal, and Ukraine again – this time catching a train in Portugal, face down to the earth, determined to document the ideological inconsistencies of the ‘European corridors’, in whose name reluctant alpine valleys are being devastated by gigantic construction that is pregnant with corruption. This latest field investigation came out as a book entitled Binario morto (Dead-end track), which provided the inspiration for a number of other works of documentation.

As usual, those who were inspired by his work are far many more than those who would acknowledge it. A few times I found myself raising the issue in public. Probably this is the aspect in which Luca’s literary arsenal proves most valuable: while it has never been packaged to the wider public, it has always opened a new path, a new perspective. His first book, La guerra in casa (‘In-house war’), remains to date the most intriguing example of a novel cum investigative journalism on the war in Bosnia: possibly the first book that was able to simply ‘tell the plain and whole truth’ – as several journalists on the different fronts acknowledged as they read it. The book stems from the polyphony of stories by those refugees whom Luca himself smuggled away from the war, hosting them in his family house on the Alps, creating a community: it provided an account of the war in Bosnia that stood at cross purposes with the narratives we were reading on the newspapers in those days.

The anticipatory character of Luca’s work is confirmed in his La frontiera addosso: così si deportano i diritti umani (‘Carrying the border: how human rights are deported’) which a few years ago shed light on Mediterranean migrations, refugees and illegal refoulement practiced by states. Likewise, his journalistic inquiry into the strategic value that the ‘miracle of Medjugorje’ had before and during the war in Bosnia, while causing rage in some zealous Catholic clerics, anticipated a debate that still makes headlines these days, as which still galvanizes tens of thousands of pilgrims keep flocking to the mainly Croatian-inhabited mountains of Herzegovina.

It is probably fair to say that Luca’s early job positions, first as editor-in-chief of the literary journal L’indice dei libri, then of the activist magazine Narcomafie, enshrine the two poles of his passionate work: journalism and literature (beside La guerra in casa he is author of three other novels). But they tell us little of how he understood his being a writer and a journalist. First of all, he was an author by ‘going there’, beginning with his first love for Czech(oslovak) literature during the 1980s, whose protagonists he went to look for in the most derelict bars, learning their language. Second, by always being loyal to his activist/militant intellectual mission, that 10 years of illness have neither been able to crack nor scratch. His last complete book, I Buoni (‘The good ones’) – is an example of that unabated intransigence: in a country as imbued with stories of ‘doing good’ and victim-selling as Italy, it tells the story of an iconic priest and the industry of good-doers he has created with dubious means. A rare example of Dostoevskijan Italian novel, it has been an object of explicit and personal attacks from many quarters, but the narrative object itself has proved to be too high for the critics and the bigots to even get to touch.

Luca Rastello has fought a battle in the name of the warmest and deepest bonds of human solidarity: scared as any human would be, he was able to guide us through the story of his struggles, and his story-telling is echoed everywhere. He had already left, and he was still teaching me how to fight on the most insidious terrain. The immense sycamores that silently witnessed our night summer conversations in the Greek island of Thassos will hear his voice again.